War of the Words

Published in Canadian Lawyer Magazine | By Lisa Gregoire | Publication Date: March 2009

“Without knowing the force of words,” Confucius said, “it is impossible to know men.” He was right of course. It seems he always is. Words start fights and stir yearning hearts to acts of bravery and bloodshed. We use words to debase others and exalt ourselves. We pray with words. We shout, organize, slander, teach, threaten, understand, share ideas in Internet chat rooms, and boast in blogs. Words of our lovers, mothers, and enemies roll around in our heads when we can’t sleep making us mad with jealousy, regret, revenge.

Words simply spoken can turn thousands toward malevolence with gas chambers. Or machetes. Which is why the preservation of a peaceful, pluralistic society like Canada hinges on outlawing hate. Or does it? Perhaps words are simply words — offensive, even forceful at times, but essential to a public discourse from which reasonable citizens in a democracy inform their personal opinions.

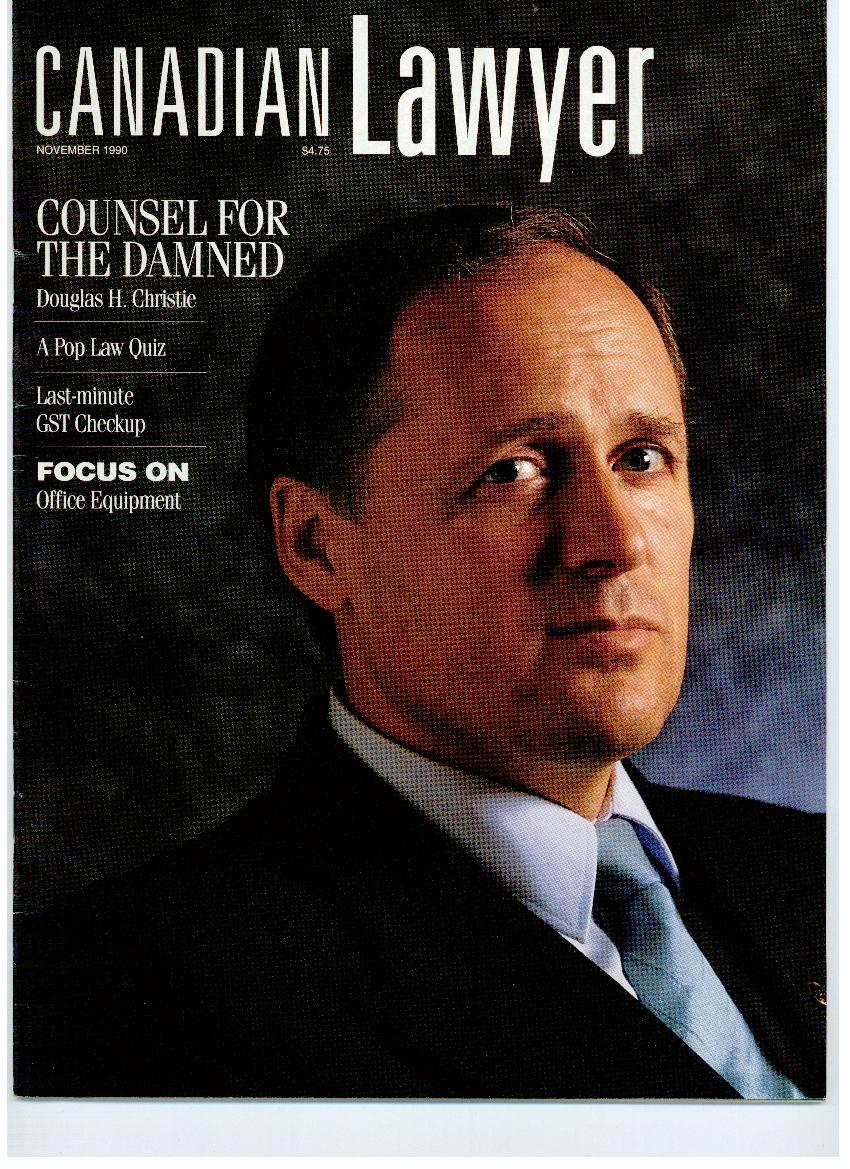

This polemic has alternately simmered and boiled for more than three decades and no two lawyers in Canada exemplify this debate more precisely than hate propaganda sleuth Richard Warman and free speech libertarian Douglas Christie: crusaders, courtroom foes, and fellow vegetarians. And though they’d cringe at being compared further, they do share one thing more: strangers want them dead.

Someone drove a truck through lawyer Doug Christie’s street-level office once. He wasn’t there at the time. Christie’s been threatened and his property has been vandalized. People have thrown rocks at him, clenched fists, and a veritable thesaurus of insults: “perverted monster” was one of his favourites. He sued for defamation in that case and lost. “They called it fair comment. I mean, where do you go from there?” asks Christie, munching bean salad in the Ottawa courthouse cafeteria during a break in a defamation suit he’s pursing against Warren Kinsella and the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation on behalf of his client, Ian Verner Macdonald, a retired foreign service diplomat.

“I believe a person should be judged as an individual. But I realize some people can’t do that and they’ve judged me according to what they think is the company I keep,” says the 62-year-old Christie, whose client roster of Holocaust deniers, neo-Nazis, and white supremacists has come to define the Victoria lawyer as much as his signature cowboy hat and boots.

Likewise, Warman might as well have crosshairs on his chest. His enemies have repeatedly posted his home address online with Google map directions, beckoning those within range to point and shoot. Notorious neo-Nazi Bill White, head of the American National Socialist Workers Party, sent Warman an e-mail once. “He said, ‘I have a Ruger P90 and its bullets have your name on it fag-boy Warman.’ It’s hard to get any more direct than that,” he says. White was indicted in December 2008 on seven counts of uttering threats, extortion, and intimidation based partly on testimony Warman gave before a grand jury in Virginia. Resulting from such threats, Warman reveals precious little about himself aside from saying he works for the federal government, obtained law degrees from the universities of Windsor and McGill, and is in his late 30s.

The clatter from this war of words reverberates into mainstream media and Parliament Hill. Obstreperous right-wing commentators Mark Steyn and Ezra Levant were both accused of hate crimes —Steyn, a Maclean’s columnist, for passages in his book America Alone and Levant, who also writes the Back Page column for this magazine, for publishing those notorious Danish cartoons of the Prophet Mohammad in the now-defunct Western Standard. Both men perpetually mourn the death of free speech and fill the blogosphere with calls to repeal s. 13, the Canadian Human Rights Act’s hate provision.

Scrapping s. 13 is a good start, says Christie. Then get rid of Criminal Code hate offences too, he says, because they unreasonably inhibit our right to speak freely about controversial topics. Other Criminal Code offences already cover conspiracy to commit crimes, counselling in the commission of offences, and threats to do bodily harm, and there are defamation laws as well, he says. Expressing opinions about race and religion, no matter how nasty, should not be a crime, he argues.

Warman, who has tracked hate groups for 20 years, disagrees and cautions against removing legal barriers. Given free reign to meet, organize, and publicize their views online and in person, he says, neo-Nazi and white supremacist groups would grow and hate-related acts of violence would as well. Like it or not, Canada has a policy of multiculturalism and has signed international protocols to uphold human rights and eliminate discrimination, Warman says. It has a responsibility to preserve a hate-free society.

Freedom of expression in Canada and the legal constraints of it have evolved over time but most scholars point to the 1965 Special Committee on Hate Propaganda in Canada — dubbed the Cohen Committee — as the beginning of the modern debate between free speech and hate speech. The committee, which included a young Pierre Trudeau, was struck in response to the growth of fascist groups in Canada only 20 years after the Second World War and Holocaust. In its report to Parliament, the committee concluded: “. . . the hate situation in Canada, although not alarming, clearly is serious enough to require action. It is far better for Canadians to come to grips with the problem now, before it attains unmanageable proportions, rather than deal with it at some future date in an atmosphere of urgency, of fear, and perhaps even crisis.”

Based on the committee’s recommendations, the Criminal Code was amended in 1970 to include s. 318 (the criminal act of “advocating genocide” defined as supporting or arguing for the killing of members of an “identifiable group”), s. 319 (“public incitement of hatred” where a person communicates statements in a public place and incites hatred against an identifiable group in such a way that there will likely be a breach of the peace), and s. 320 (allowances for the seizure of hate propaganda material for distribution or sale which, after 2001, included computer files and web sites). Charges under these three provisions cannot be laid without consent from provincial attorneys general.

A couple of other landmarks dot the road of the current debate. The Canadian Human Rights Act, passed in 1977, included that controversial s. 13 provision making it discriminatory for a person or group to “communicate telephonically” any matter “that is likely to expose a person or persons to hatred or contempt.” That too was amended in 2001 to include communicating via the Internet.

Under the Human Rights Act, you can be guilty of a s. 13 offence even if you didn’t intend to cause harm, and truth cannot be used as a defence. Opponents say this unfairly hobbles those accused of breaching s. 13, but advocates say since it’s nearly impossible to get hate crime charges laid under the Criminal Code, s. 13 is critical for stifling the rancorous and potentially harmful actions of neo-Nazis, white supremacists, and others. A young human rights activist-cum-law student named Shane Martinez is adamant about that, but more on him later.

After the passage of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms in 1982, some free speech devotees saw an opportunity to slay s. 13, Doug Christie among them. Representing John Ross Taylor, who was found guilty by the Canadian Human Rights Tribunal of disseminating hate messages via a telephone answering machine, Christie appealed the case to the Supreme Court of Canada in 1990. He lost — but barely. The court ruled, in a 4-3 decision, that s. 13 was a reasonable and justifiable limitation of rights under the Charter. “I think they went the wrong way. And I think they realize they went the wrong way and they’re going to reverse it if it ever gets back there,” says Christie. “If the government or the courts decide to regulate what we think and what we speak, they will be inherently corrupted by their own biases and bring the administration of justice into disrepute. . . . It’s an area they should stay out of.”

The federal Conservatives agreed. At its November 2008 convention, it adopted a resolution to remove authority from the Canadian Human Rights Commission to investigate and adjudicate s. 13 complaints. But a beleaguered Stephen Harper has nudged that resolution to the back burner. When asked by Maclean’s in January whether the government planned to amend the act, Harper told editor Ken Whyte, “The government has no plans to do so.” He explained: “It is a very tricky issue of public policy because obviously, as we’ve seen, some of these powers can be abused. But they do exist for valid reasons, which is obviously to prevent public airwaves from being used to disseminate hate against vulnerable members of our society.” The PM’s use of the word “airwaves” was confusing since s. 13 deals only with the telephone and Internet, but nonetheless, his intentions seemed clear.

That hasn’t stopped Keith Martin, a Liberal MP from Esquimalt-Juan de Fuca, B.C., from taking up the torch, introducing a pair of motions in November calling for s. 13 to be deleted and for public hearings to review the act, the commission, and its tribunal. Martin says he hadn’t paid close attention to the Human Rights Commission until he got a call from a constituent. “I was quite appalled at how the act was being used to, in some cases, bludgeon freedom of speech,” he says. “The act was going far beyond protecting individuals from hate speech and at times, making almost arbitrary decisions to go after people who said things that were deemed by a small group to be offensive.” Sweeping generalizations like that make Warman flush red with aggravation.

According to the commission’s web site, 70 s. 13 complaints were filed between 2001 and April 2008 and, as of that month, only 13 had been upheld by the tribunal. Eleven of the 13 were filed by Warman, who worked as a human rights officer and legal counsel for the commission from 2002 to 2004. Warman says he filed complaints before he started working for the commission, during, and after he left, but adds he was not involved with the complaint process or the investigations. His detractors insist otherwise and accuse him of abusing his power and connections to grind axes. According to one insider, Warman’s preoccupation with s. 13 makes some commission members uncomfortable. His response is simple: the legislation is there so why not use it? “If you know there are people calling for the genocide of your neighbour, you have a fundamental moral and ethical duty to do whatever you can to stop it,” he says. “I think it would be a failing to my profession as a lawyer not to.”

Peruse the tribunal’s recent decisions and it’s hard to find any of the “arbitrary” cases Martin refers to. In each decision, the tribunal cites examples of online cultural conspiracies (by “Niggers,” “Injuns,” “Chinks,” etc.), vile depictions of First Nations, gays, Hindus, blacks, Muslims, Jews, etc., and threats to harm members of those “sub-human” groups. Postings to a Canadian Nazi Party web site were the subject of a 2007 complaint by Warman against Bobby Wilkinson. The tribunal’s decision cited repeated calls to kill “niggers, Jews, and faggots,” including this post: “The only faith I have left in this country is that the KKK and White Power grops [sic] all across the nation will fix this terrible mess with genocide.”

It is nasty, threatening content, says Doug Christie, but just words in the end, emitting from the fringes of society. “You’re never going to have free speech issues in regard to popular people because no one’s ever going to shut them up,” he says. “Controversy is where free speech becomes an issue. And you’re not going to have controversy if what the person says is popular. Free speech is for the unpopular. It’s never free speech until it is unpopular — it’s just accepted speech.”

In the self-diagnosing, porn-populated, face-space-wiki-tube universe we call the Internet, “accepted speech” seems to be getting freer and more controversial all the time. People say just about anything online including half-truths and outright lies. And that’s just what we can find with ease. Dig further. Register in Ku Klux Klan and neo-Nazi chat rooms, and you’ll find conversations that are more than just offensive — they’re disturbing.

“It may mean that mass distribution is not actually the most significant factor,” says Richard Moon, a University of Windsor law professor who authored an October 2008 report on s. 13 for the Canadian Human Rights Commission. “In fact, what might be a concern are these isolated, insular groups that are exchanging and feeding off each other’s increasingly extreme claims, assertions, challenges, and so forth. . . . What gets said is outside of critical public scrutiny.”

Despite his concerns — and much to the surprise of Christie and his cohorts who thought it would be a whitewash — Moon’s report recommended s. 13 be deleted and hate crimes be left to Criminal Code prosecution. “There are, of course, some potential drawbacks to an exclusive reliance on the Criminal Code hate speech provisions,” Moon wrote. “These include the higher burden of proof, the requirement that the attorney general of the particular province consent to prosecution, and the lack of experience on the part of police and prosecutors in pursuing hate speech cases.”

To mitigate these drawbacks, the report — researched and compiled under a three-month time constraint — recommends studying why attorneys general, for instance, have been reluctant to give consent for hate crime prosecutions. Moon also suggests each province establish a hate crime team like Ontario’s, composed of experienced police officers and Crown prosecutors.

“I always wanted a pony growing up and I never got one,” says Warman. “I would love for every province to have a dedicated hate unit that co-ordinated with Crowns, that had reasonable access to the attorney general in their province or territory, that doesn’t rotate its staff every couple of years, and that has an appreciation that words can be used for evil purposes to create the preconditions that are necessary for attacks and violence against the target community and that understands the history of that. But it ain’t gonna happen.

“Dick Moon talked to me when he was doing his report,” Warman continues. “He said, ‘Some people have suggested this should all be left up to the police,’ and I said, ‘I’m sure they have and the only people who could ever possibly suggest such a thing would be people who’ve never actually tried to have criminal charges laid in connection with hate group activity.’ I have, in a number of cases, and I don’t want to say it’s virtually impossible but it is so close as to be nearly indistinguishable.”

Even Ernst Zundel, Canada’s most infamous Holocaust denier and one of Christie’s clients, was spared. “It’s said that at the time that Ernst Zundel was operating in Canada, and members of the Jewish community of Ontario really wanted a prosecution brought against him under the hate promotion provision,” says Moon, “that then-attorney general Roy McMurtry declined to give his consent because he was concerned the prosecution would just become a vehicle for Zundel to promote himself and his ideas. Now, maybe there was something to that. I’m not sure I think that’s right, but it’s a legitimate perspective.” Zundel was convicted only of “spreading false news,” a crime that was later struck down as unconstitutional by the Supreme Court.

And speaking of unconstitutional, Marc Lemire, an outspoken Canadian white supremacist and former leader of the now-defunct Heritage Front, is taking aim at s. 13 by forcing the Canadian Human Rights Tribunal to consider whether the section infringes his Charter rights. He also claims ss. 2(a) and 7 of the Charter — freedom of conscience and religion, and the right to life, liberty, and security of the person — are also compromised by the Canadian Human Rights Act. (Lemire is facing a s. 13 complaint filed by Warman for material posted on his freedomsite.org web site.) Lemire’s challenge caught the attention of Shane Martinez, a supporter of the Anti-Racist Action collective in Toronto and now a law student at St. Thomas University in Fredericton. He recently wrote a research paper on Lemire. “The dangerous irony presented by Lemire’s Charter challenge must be exposed for what it truly is: an attempt by a leading member of Canada’s far-right movement to use the country’s most powerful human rights legislation to protect his continued violation of the human rights of others,” Martinez wrote.

Martinez feels community activism is the best way to staunch the growth of hate groups. If that doesn’t work, legislation comes in handy. “When hate manifests itself in our communities — through hate crimes, vandalism, recruitment in the streets — definitely organizing action at the grassroots level is a necessity, but for hate on the Internet, s. 13 is arguably one of the best tools we have right now. It’s an important piece of legislation which keeps these groups from reaching as broad an audience as they otherwise would.”

While the passion, personal sacrifice, and commitment from both sides of the debate are admirable and even astonishing, the struggle between opposing rights is sometimes sullied by righteousness, caricature, and one-upmanship. Warring web sites post accusations about their nemeses; mainstream media pick up the thread; defamation suits flutter like leaves in autumn. Average Canadians are likely more concerned about the plummeting value of their mutual funds than the intellectual acrobatics of who has the right to say what about whom — at least the ones not threatened by hate-mongers.

Regardless of where you stand on the debate, and until Canadian law changes, those who promote and disseminate hateful propaganda will face censure. For every person offended or angered by that fact, there are other Canadians who probably feel tremendous relief.